Korean War POW Recounts Experiences

While some young men were drafted into military service, Candido Mascarenas convinced his parents to sign his enlistment forms so he could join the Army at 17. Little did he know he would be captured by the North Korean army and become a prisoner of war by the time he was 19.

After basic training, Mascarenas was assigned to the 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division, and stationed in Kyoto, Japan. With only two months before he was due to return home, war broke out on the Korean Peninsula.

Mascarenas’ infantry regiment was one of the first to deploy and enter South Korea. The North Korean forces had already advanced below the 38th parallel, pushing deep into southern territory.

“We were supposed to fight and hold back the North Korean army for about 12 days until more troops could arrive. Our division did not have the strength to hold them back. We were the first ones to clash with the enemy, but we were slaughtered,” Mascarenas said.

Though they held on as long as they could, Mascarenas’ platoon was captured on July 14, 1950.

“They tied us up, took us back away from the front lines. And then from there, the suffering started,” he said.

As the enemy moved them farther into the interior, the prisoners encountered the slain bodies of other American soldiers who were shot with their hands tied behind their backs.

“All of us were afraid that they were going to do the same thing to us. But they didn’t,” said Mascarenas.

When more U.S. forces entered South Korea and began pushing the enemy back, the Chinese came to the aid of the North Koreans. In the meantime, the enemy kept the prisoners out of reach of rescue. Mascarenas recalls that, at times, they could see the campfires of their compatriots about 30 miles away. Help was close but not close enough.

Eventually, Mascarenas and his fellow POWs were transferred to the command of a North Korean officer known as “The Tiger,” who marched them across rugged terrain for several days. Many prisoners died during the journey.

“We started this march and it ended up being a death march. They shot about 90 to 100 of our guys,” said Mascarenas.

The now-infamous Tiger Death March took its toll mentally and physically on the men, who marched through snowstorms high up into the mountains while carrying the wounded and sick. Along the way, the guards ordered them to put the infirm men in a ditch by the side of the road, where they were shot and killed.

“I volunteered to bury our dead. But we couldn’t dig any trenches because the ground was frozen solid. So we just buried them in ditches and covered them with branches, snow and whatever we could find. I don’t think those men were ever accounted for because they got left out there in the wilderness,” he reflected.

Mascarenas’ platoon, as well as many other U.S. servicemen, found themselves in Chinese prison camps where they experienced interrogations, brainwashing and torture.

“They would tell us how rotten our government was and how good communism was—trying to convert us to communism. A lot of guys did believe. There were about 21 guys who stayed back after we were released,” Mascarenas said in disbelief.

“I got tortured quite a few times by the Chinese because I didn’t cooperate,” he said, his voice breaking. “Finally, the peace armistice was negotiated in July of 1953. One company at a time was being taken out of the camps, about 125 guys each time. I was in the last group to be taken out. The day the enemy released me was Aug. 28, 1953.”

Candido Mascarenas was one of the first to enter the Korean War, and he was one of the last men out. However, he was not sent home right away. The American government wanted to gather information about what had happened during his captivity, so he and others from his platoon were kept in Seoul for a few more days.

“We filled out lots of blanks to record the details of the men we knew who had died during combat and those who might still be missing,” he said.

Of the men from the 24th Infantry Division who entered South Korea, 402 were killed and 29 were missing in action. Thankfully, Mascarenas made it out alive, but the effects of being a prisoner of war had left their mark on him.

Returning to his hometown of Placita, New Mexico, Mascarenas and another friend who had served as a pilot were warmly welcomed by the community, which held a dance in the high school gym in honor of its two local heroes. Upon arriving at the dance, Mascarenas was instantly overwhelmed by all of the people—the sights and sounds.

“It started to turn on me. I couldn’t believe it. All of a sudden, I felt so nervous,” he said.

Feeling lost, Mascarenas decided to reenlist in the Army and was ultimately stationed at White Sands, New Mexico, where he met and married his wife, Lucille. However, he didn’t discuss with his new bride the nightmares that had begun about a year before his release.

Feeling lost, Mascarenas decided to reenlist in the Army and was ultimately stationed at White Sands, New Mexico, where he met and married his wife, Lucille. However, he didn’t discuss with his new bride the nightmares that had begun about a year before his release.

“The nightmares were always of someone trying to kill me. One night, I had one of those terrible dreams and I started hollering out. I had never told my wife anything about the nightmares. She was scared,” he said as he broke down weeping. “I had to tell her about my problem. Thankfully, she stood by my side through it all.”

Many military veterans develop post-traumatic stress disorder following combat. It also affects their loved ones, especially spouses and children. Unfortunately, some veterans don’t have support to turn to in their time of need. Others seek help, but PTSD can often be misunderstood.

“Back then, we didn’t have the help we needed. When I got out of service, the VA didn’t acknowledge my PTSD. I had a doctor tell me that I was just an alcoholic. They didn’t believe me,” Mascarenas said.

“Actually, Disabled American Veterans—they’re the ones who helped me, you know, helped me a lot to get through,” he said.

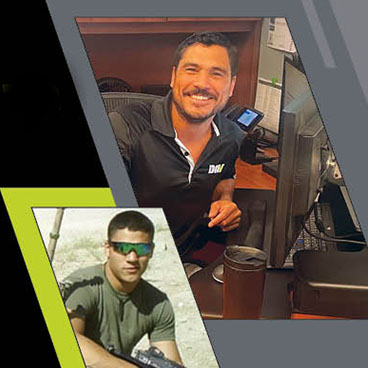

Mascarenas found DAV and became a life member in 1976. DAV steps in as a support network for many veterans who suffer service-related trauma.

Largely due to research gathered through the DAV-funded Forgotten Warrior Project, PTSD was finally listed in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistics Manual of Mental Disorders III though it wasn’t formally recognized as a disability until 1980.

“On account of veterans who bravely sought assistance with mental health challenges, DAV gained institutional knowledge that led many to receive justice in their fight for benefits,” said DAV National Adjutant and CEO Marc Burgess.

“We are indebted to our fellow veterans who are POWs, such as Mr. Mascarenas. They have suffered tremendously from the invisible wounds of wartime service—including moral injuries,” Burgess said. “What an honor for DAV to be at the forefront of getting PTSD recognized and codified as a disability in our federal regulations. This was a major victory in keeping our promise to America’s veterans.”

Will you join us in keeping the promise? You can support our nation's heroes such as Candido Mascarenas by making a gift to DAV today.