Alive Day: Vietnam War veterans mark 50th anniversaries

The landmark commemoration of the Vietnam War began in 2012 and is now nearly at its midpoint. This year, DAV Magazine will feature members whose lives were forever changed a half century ago.

By D. Clare

Jim Sursely had never thought about joining the military. His father was in the Army Air Corps in World War II, but his focus as a teenager had been on sports – football, baseball, and basketball.

But in May of 1966, the war was on the minds of many. While driving down the street in his hometown of Rochester, Minn., he saw a sign that said “Uncle Sam needs you.” He went to an Army recruiter and within three months was inducted into the military.

“My motivation was to probably go to do three years … come home and use the G.I. Bill to go to school and play college football,” he recalls.

Sursely wasn’t challenged physically by boot camp at Fort Polk, Louisiana. And track vehicle training school at Fort Sill was a breeze. But when he was sent to Germany, he felt like he was out of the game. “I wasn’t a very good garrison soldier,” he recalls. So, he volunteered for duty in Vietnam. He arrived in March of 1968, a month after the Tet Offensive. American forces had marked the bloodiest week of the war when 543 Americans were killed and 2,547 had been wounded.

He was assigned to F Troop, 17th Armored Cavalry Division, which was a part of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade, in the Queson Valley, 17 kilometers southwest of Da Nang. He reported to his first sergeant and asked where the motor sergeant was. “He said, ‘Son, we don’t actually have a motor pool, but we are going to get you a toolbox. You’ll be a machine gunner in the third platoon. But be sure and use that toolbox whenever they need you.’”

By January of the following year, he’d been involved in fierce combat against Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army soldiers. He’d been promoted twice. On the eleventh of the month, he was setting up for a night operation, making sure his unit’s claymore mines were in place.

“I stepped on a landmine which resulted in the amputation of both of my legs and my left arm,” he said. In an odd way, the force of the blast and the fireball that came with it saved his life, cauterizing his wounds nearly as fast as it removed the limbs.

“I remember going up in the air, coming back down and lying flat on my back. And I remember reaching down with my good right hand. And I touched what would be like mid-thigh on my right leg, which kind of gave me a feeling that I was probably okay and still intact. I had absolutely no idea that I'd lost [three] limbs at that point.”

In that same instant, the plans Sursely had for his future were forever changed. Three days later, he woke up in Japan for a fleeting moment of consciousness. Weeks and 12 major surgeries later, he regained consciousness in time to be sent stateside. “They started feeding me whole food, getting ready for me to take the flight back to the states and that's when I could look with my own eyes at whatever was missing or what I had left. So, like 30 days after my injuries was when I totally and completely realized what I had lost.”

While thankful to be alive, Sursely was in a state of shock about his future. He wasn’t around disabled people while growing up and it was hard to imagine what he could do to support himself. This was before the Americans with Disabilities Act and places like his hometown, he said, were not easily accessible. He recovered at Fitzsimons Army Medical Center in Aurora, Colorado. By the end of the year, he’d been medically retired from the military and returned to his family.

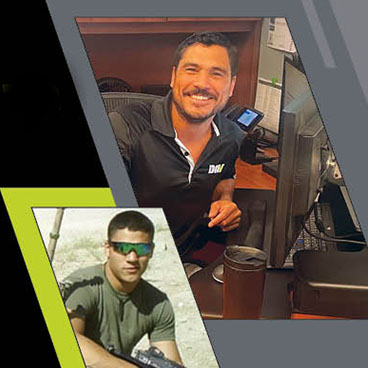

Football may have been out of the cards, but school wasn’t. Sursely studied to be a CPA, but the pre-computer world of accounting was too tedious for the former combat soldier. He moved to Fla. where new construction brought greater accessibility. He went into real estate. To date, he is the top active seller of homes in the Apopka, Fla. community he calls home.

He found he could succeed in relationships with women, dated and eventually married. When his first marriage ended in divorce, he dated and married again. He was confident. He’d grown and evolved. Today, he and his wife Jeannie run their business. He has four children, 12 grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

He joined DAV in 1970 and transferred at Jeannie’s behest to Chapter 30 in Sanford. He enjoyed the camaraderie and tried to give back. “They were remodeling the building on a couple of different occasions,” he recalled. “There’s not much I can do to help remodel but come down and be moral support and hand a tool or something up the ladder if they’re working. I always tried to do that as much as I could. And I think they viewed me as wanting to belong. It didn’t make a difference if I couldn’t climb the ladder.”

After becoming a leader in his chapter and at the state level, his fellow veteran leaders, several of whom were past national commanders, groomed him for the big stage. He walked the line and was elected national commander in 2004. Though he’s met with presidents and dignitaries, he’s most proud of the opportunities he’s had to talk with his fellow veterans. He teaches them, and his fellow citizens, about the value of accepting events from the past while constantly challenging perceived limitations.

Through DAV’s partnership with Boulder Crest and the Gary Sinise Foundation RISE Program, he connects with younger veterans who are going through challenges he’s faced over the last five decades.