A Marine helps his own

Vietnam veteran turns to DAV for help with lasting effects of war

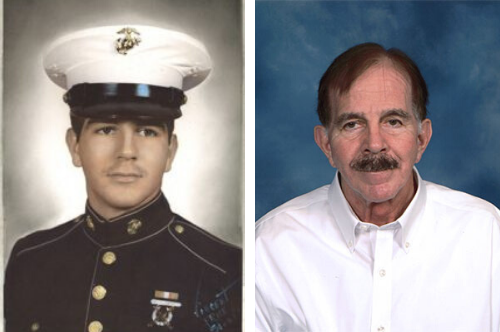

Dennis Reichert struggles daily with what he experienced in Vietnam. Memories of fierce combat haunt the Marine, as do images of the weapons, flak jackets and canteens stacked row-after-row, each representing an American injured or killed on the battlefield.

Reichert enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1966, after one year of college. He was motivated to go to Vietnam after learning about the plight of South Vietnamese civilians.

“I read the stories in the paper, and I was going to try to save people from being enslaved by communism,” he said. “That’s the main reason I enlisted in the Marine Corps, to save South Vietnamese.”

After boot camp and infantry training, he got his wish and found himself in South Vietnam, not far from the North Vietnamese border, which proved to be a dangerous area.

“The enemy would come straight over the border, or they would go west through Cambodia and Laos,” recalled Reichert.

One day, in particular, stands out as especially traumatizing. While passing through the coastal city of Huế, Reichert noticed a distinctive stench filling the air, becoming more horrid with each passing step. As his element turned a corner, he saw the source of the smell: a dead body that had been steamrolled by tank treads.

“That was my first time smelling and seeing real death,” said Reichert.

It would not be his last.

Going on patrol, coming into enemy contact, and calling in air support became a routine occurrence. To keep eyes on enemy movement, the noxious herbicide Agent Orange was sprayed to clear the area of vegetation.

“It would make sense for these areas to be defoliated, so our jets and other forces could see the North Vietnamese entering South Vietnam,” said Reichert. “Somewhere along the line, I came into contact with Agent Orange.”

Reichert was in-country for nine months before he was injured in combat, ending his time on the front lines. While approaching a village, the Marines began taking small-arms fire by enemy troops who were exceptionally well dug-in. “They would hop up,” said Reichert, “and kill the Marines at the top of the column.”

The Marines took cover and called in close air support.

After the explosions settled—which Reichert said was “so intense that trees would go sideways”—the enemy was still there. The element was lying prone on the ground when a Marine about six-feet from Reichert was shot.

“For some reason, I was looking at him when the bullet hit his head,” he recalled. “He slowly sank into the ground, and I knew he was dead.”

Not long after that, a piece of shrapnel flew across the field, hitting Reichert’s leg. He and the other wounded were evacuated to a medical ship at sea.

Reichert was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps in August 1968, but the battle-scarred veteran continues to live with the effects of the Vietnam War. More recently, he began noticing physical tremors, which he suspected was Parkinson’s disease—an illness linked to Agent Orange exposure. On the advice of others, he visited DAV at the St. Louis VA Medical Center at Jefferson Barracks in February 2018.

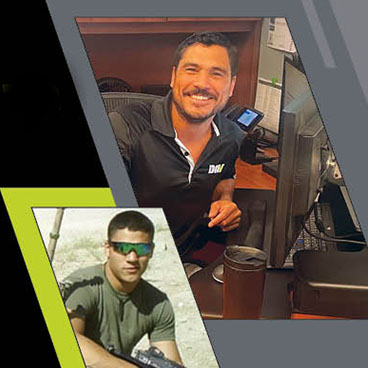

That’s when he met fellow Marine and Afghanistan war veteran, Michael Franko, who, at the time, was a DAV Department of Missouri service officer. The two quickly bonded over their shared familiarity of war, despite serving decades apart. Although Parkinson’s is what brought Reichert into the DAV, he asked Franko if “it was okay” to have PTSD.

“When you look at somebody who has been through the thick of it, they don’t always have the life in their eyes,” said Franko, who submitted claims for VA benefits and compensation.

After Reichert received a Parkinson’s diagnosis in May 2018, Franko walked him through what to expect with mental health examinations and explained that he was only a phone call away if he needed any help. Reichert would frequently visit Franko throughout the claims process, and the two would swap stories, as veterans often do.

Franko became a DAV national service officer in July of that year, but still kept up with Reichert’s claim and would frequently update him on its progress. In September, Reichert received his final decision letter granting him VA benefits and compensation for Parkinson’s disease, PTSD and his wounded leg.

“He’s finally getting the treatment he deserves,” added Franko. “You could tell he walked a little taller and was much happier.”

Franko says he was driven to become a service officer to give back to veterans like Reichert.

“In my heart and mind, I feel like I won a battle for this individual,” he said. “Before Dennis received the decision, he appeared to be a shell of himself. Once he got a confirmed diagnosis, you could see he wasn’t just going through the motions anymore.”